S1: Episode 37 - Jack Levine

Episode Information

[Intro Music]

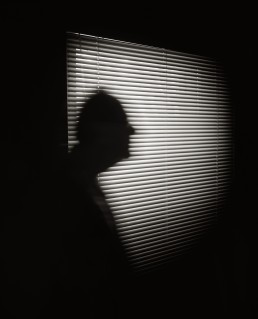

Narrator: Welcome to My Heart is Not Blind. Narrative histories about blindness and perception. A traveling exhibition and book published by Trinity University Press, supported by Kronkosky Charitable Foundation, edited and hosted by Michael Nye. Stories are often found, resting along the edges of surprise and revelation. Every person, every place is a map to somewhere else. Episode 37, Jack Levine.

Jack: My father lost his sight when he was 52. He turned blind in 24 hours. They conjecture. It was an aneurysm. My first name is Jack, named for Jacob, my father’s father. And I am fully sighted. I’ve seen for two people my whole life. I actually think I am double-sided. It’s the opposite of being blind. The most important image I have of my father was astonishment of his life’s journey. He saw lots of tragedy. He escaped the woods of Russia with his life. When he was 14, the czar sent out troops of horsemen to basically ravage the villages, burn the homes, rape the girls, and capture the boys. For target practice they ran the boys through the woods. So my father and his friend, Benny, they packed up their burlap sacks and went through Poland to earn enough money to get on a boat and emigrate to the United States. And that happened in 1908.

My childhood home was in Long Beach, New York. We went to the beach most days of the week, and the kids that I hung out with wouldn’t come to our house because I think they were afraid of my father. He was such an odd person. They were afraid of his blindness. I think they were afraid of his age. The fact that when I was 10, he was 70. I, I just, it didn’t compute for these kids. Their grandfathers came to visit them, and they were 10 years or more younger than my father. So the words they used were not so much derision, it was just disbelief. There is in all of us a fear of darkness of the unknowing. And as a sighted person, I would play blind as a child to try to know what it felt like. And a minute in, I had to open my eyes.

I could not stand it. I lived with a blind man who was blind for over 30 years. Blindness is not the last act. There are more scenes to your life and more accomplishments. So what I know for sure is that my father’s willingness to learn, his willingness to accept new ideas was not hampered by his blindness. While some kids took music lessons, I didn’t. Some kids were athletes. I wasn’t. My skillset was the English language. I was raised to serve my father as his second set of eyes, as his reader. They were handwritten letters from immigrants. I mean, this was, this was not an easy read. This was not great penmanship. And I was frustrated by that. And I would actually sound out letters. It was very rudimentary, but he was so curious to know what his friends were saying. My oldest brother, who was born in 1922, my half-brother once told me that he thinks our dad gave away three quarters of anything he ever earned to his workers and to causes.

He was a cause maniac. My father supported the civil rights movement. There is no such thing as advocacy DNA. They haven’t found it yet on the helix. But if there is something inherited about being an activist or being an advocate, I, I think I got a full measure of that. One set of skills my father developed way before his blindness was the capacity of touch. His business was in very fine embroidery on women’s fancy gowns. He used to test the seamstresses skill by touching the stitching. So when he lost his sight, he had already gotten used to the sense of touch. He was a braille genius. He knew how to touch the dots. I learned to love who my father was. There was not a lot of overt affection. I don’t really remember hugging and kissing him much. I have no doubt that my capacity to read well, write well in some ways, speak well, was rooted all of it in my duties to my dad, starting at age eight. So little did I know until my full adulthood that his blindness was a gift to me. My anger to some degree, my frustration with having to read from my father transformed into, uh, an appreciation of that gift in my adulthood.

[Outro Music]

Host: Jack has been an advocate all of his life for his father. For those with vision loss and for fairness and justice, he found a comfortable process. He said There’s a power in bringing people together. Democrats, republicans, individuals and organizations. I collect information and then I find people in groups who can use that information. He took a stand against child abuse, a 40 year career as an advocate for Florida’s children and their families. Jack and his wife Charlotte live in Tallahassee, Florida. They have two sons and a granddaughter. He said, much of my creativity comes from working in my garden. There’s a strong connection between advocacy and gardening. His interest in reading, speaking and public policy was rooted in his childhood. He read to his father, who was blind. His right arm helped guide his father to unfamiliar places.

Join us next week, two new episodes will be released. Please subscribe, rate, and review this podcast. You can also go to my website, michaelnye.org/podcast. for portraits and transcripts, thank you for listening.