San Antonio photographer Michael Nye explores blindness in book, Witte Museum exhibit

The San Antonio Express News

by Deborah Martin

Qusay Hussein lost his eyesight in a car bombing in Iraq that killed 16 people.

Ann Humphries lost her vision gradually over about 20 years, the result of a hereditary condition that was diagnosed when she was in her 30s.

And musician Ray Paz was born blind, his white eyes scaring the other children when he was growing up.

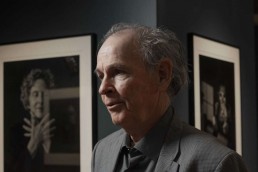

Hussein, Humphries, Paz and 42 other people from across the country who are blind or have deep bonds to people who are visually impaired told their stories to photographer Michael Nye. They talked about how they lost their sight, how they navigate the world as a result and how that impacts the way sighted people view and interact with them. Nye is now sharing those stories and his portraits of those who told them twice over: In “My Heart is Not Blind: On Blindness and Perception,” an exhibit at the Witte Museum, and in a book of the same name that Trinity University Press is publishing in February.

In the exhibit, each of Nye’s powerful black-and-white photographs is paired with a roughly five-minute recording drawn from the interviews. The recordings can be heard through headphones that hang below each image. Listening to them creates a sense of intimacy, which is intentional.

“I really worked on my audio,” said Nye, 70. “I feel like they’re present with you.” He spent up to four days with each of the people featured, talking to them about their lives and taking photos.

“I think one of the hardest things is trying to have fidelity to each person’s experience — not romanticize it, not make it worse, just try to be consistent with what their experience is,” he said.

He also aimed to present a broad range of perspectives to paint as complete a picture as possible of what it is like to be blind. The experiences of those who are blind from birth are very different from those who lost their vision later in life, he said. And someone who lost their sight suddenly has a different perspective than

someone who lost it gradually.

Blindness itself takes different forms, too. Some of the people in the exhibit are able to detect some things

visually; others are not.

“It’s complex,” Nye said. “Like all of our lives are complex.”

Nye also included a couple of sighted people with blind loved ones. Jack Levine talks about his experiences with his father, describing serving as his father’s eyes as being “double-sighted.” And Christina Wright talks about the pain of learning that her son Weston had been born blind and then of her fierce determination to make sure he has a full life.

The title is drawn from Nye’s interview with Frances Fuentes, a single mother who lost her sight when her son was 11 months old. She talked to Nye about her battle to raise the boy by herself, something some people thought she wouldn’t be able to do because of her blindness. “I fought with my tears,” she told Nye. “I started crying so much for my son. I had to show them how much I loved him, how much I needed him. Being blind, it’s not an obstacle because my heart is not blind. Having a kind heart, a loving heart, is more important than being blind.”

“My Heart is Not Blind” follows Nye’s earlier projects dealing with teen pregnancy, hunger and mental illness. All of those exhibits toured, and Nye is now reaching out to museums across the country for the new show. His hope is that the exhibit will help dispel prejudices toward and misconceptions about blindness.

He became more convinced than ever of the need for that when he was shopping the book around to publishers. In the text, each of the portraits is accompanied by a narrative drawn from Nye’s interviews. The manuscript was given to “blind readers” — people who assess manuscripts with no knowledge at all about the author — and he’s still floored by one of the responses.

“This one person wrote back, ‘I found these narratives from the blind and visually impaired to be so articulate I questioned whether these stories are really the sentences spoke by these participants. Would each of these participants recognize these words as something they actually said?’

“That’s what they have to deal with,” Nye said. “This is why this is a fight. This is really important. It’s not about Michael Nye’s exhibit. It’s about discrimination. It’s about justice. It’s about fairness. It’s about those issues that really matter. And that’s why I want this exhibit to travel.”

He’s been working on the project for about seven years, though the idea for it began germinating about three decades ago. He was invited to give a gallery talk to some blind students during an exhibition of his work in Saudi Arabia. The experience stayed with him.

“It was profoundly different,” he said. “Their attention, their listening — it almost changed the air. I had never experienced anyone really listening with just full presence. And I thought to myself, I would love to have conversations with these individuals. What do they know that I don’t? What’s it like to focus on other aspects

of your senses?

“And they asked questions like – it’s in my introduction (to the book) – what’s black and white mean? Why are you a photographer? What does this photograph mean? What’s beauty that’s not visual? How does anyone understand the world outside themselves blind or sighted?”

Nye asked similar questions when he finally decided the time was right to explore blindness and perception. One of the first people he spoke to about it was Larry Johnson, a San Antonio-based writer and motivational speaker who lost his sight as a baby. Johnson and Mike Gilliam, president and CEO of the San Antonio Lighthouse for the Blind & Visually Impaired, helped Nye connect with people to photograph and interview.

“He allowed me to listen to some of (the recordings), and I was very, very impressed and very moved by their comments and conversations,” said Johnson, 85. “Many of these people were folks that I had known for a very long time and had recommended to Michael, so hearing them speak with such depth and with such honesty

was very revealing and very profound.”

Johnson himself took part as a subject, as well. He is hoping the project will create empathy and dispel some of the fear that sighted people have about blindness.

“I do a lot of sensitivity training workshops, and I am very much aware of the fact that most people consider blindness as almost as scary as death,” he said. “It is something that is hard for someone who has sight to really understand, how you could continue to live and be satisfied living in an environment where you no longer can see. And, in fact, I can tell you that my wife, who is now deceased, we were married for 47 years and even she feared blindness, even though she lived with me all those years.

“And so, I’m hoping that, by listening to the conversations of the various participants, that it will reassure people and it will allow them to see, if I may say, to really see, people who are blind in a different light.”

Among the people whom Johnson suggested that Nye reach out to was Natalie Watkins. Johnson had gotten to know her through the Alamo Council of the Blind, an advocacy group. Nye visited with her twice, and there are two portraits of her in the show. The first time he talked to her, she still had some vision, though she was legally blind; seven years later, she said, she had lost her central vision completely, the result of retinitis pigmentosa, a progressive disease that was first diagnosed when she was a teenager.

Talking to Nye at those very different points in her life was helpful, she said. Among other things, she was able to detect some of her own biases.

“I was so able-ist,” said Watkins, 45, who is working on a project to help blind and disabled people increase their marketability. “I definitely felt like I was worth more with sight and it took a lot of soul searching and a deep evaluation of my personal philosophy to get to a point where I realized a person’s worth is not based on what they can ‘do’ in the same manner that everybody else does it. It’s amazing how entrenched that belief system gets in our minds.

“Being part of Michael’s project helped me get some perspective on that. It had this really beneficial impact on my life — it was almost a therapeutic benefit. When you’re living with something on a day-to-day basis, you don’t often get the opportunity of getting a broad perspective on what you’re going through.”

Like Nye and Johnson, she hopes the exhibit helps those with sight shake their misconceptions about blindness.

Marise McDermott, president and CEO of the Witte, already has gotten a sense of the potential power of the exhibit.

“We did bring in some children, some 10-year-olds, and they were so moved,” McDermott said. “There were some children with special needs, and one young boy said, ‘I’m so glad you brought this exhibition because I see me.’”

Nye debuted his earlier projects at the Witte, as well, a point of pride for the museum.

“Each of these exhibitions brings to light the way people live,” McDermott said. “All of us live extraordinary lives in one way or another, but often we focus on the ordinary and not the extraordinary. And this is such a great opportunity to hear people’s versions of their lives. And I think this exhibition really provokes the critical question of what is perception, what is seeing.”

“My Heart is Not Blind: On Blindness and Perception” opens Saturday and can be seen through March 31 at the Witte Museum, 3801 Broadway. Nye will give a talk about the show at 6 p.m. Jan. 23. Tickets cost $15 for Witte members and $25 for non-members. Info, wittemuseum.org.

dlmartin@express-news.net | Twitter: @DeborahMartinEN

Deborah Martin is an arts writer in the San Antonio and Bexar County area. Read her on our free site, mySA.com, and on our subscriber site, ExpressNews.com. dlmartin@express-news.net | Twitter: @DeborahMartinEN